As goods of all shapes and sizes journey from factory to doorstep, chances are they’ve stopped at a warehouse along the way—likely several of them. The sprawling structures are waypoints in the logistics networks that make e-commerce possible. Yet the convenience comes with tradeoffs, as illustrated in a recent study.

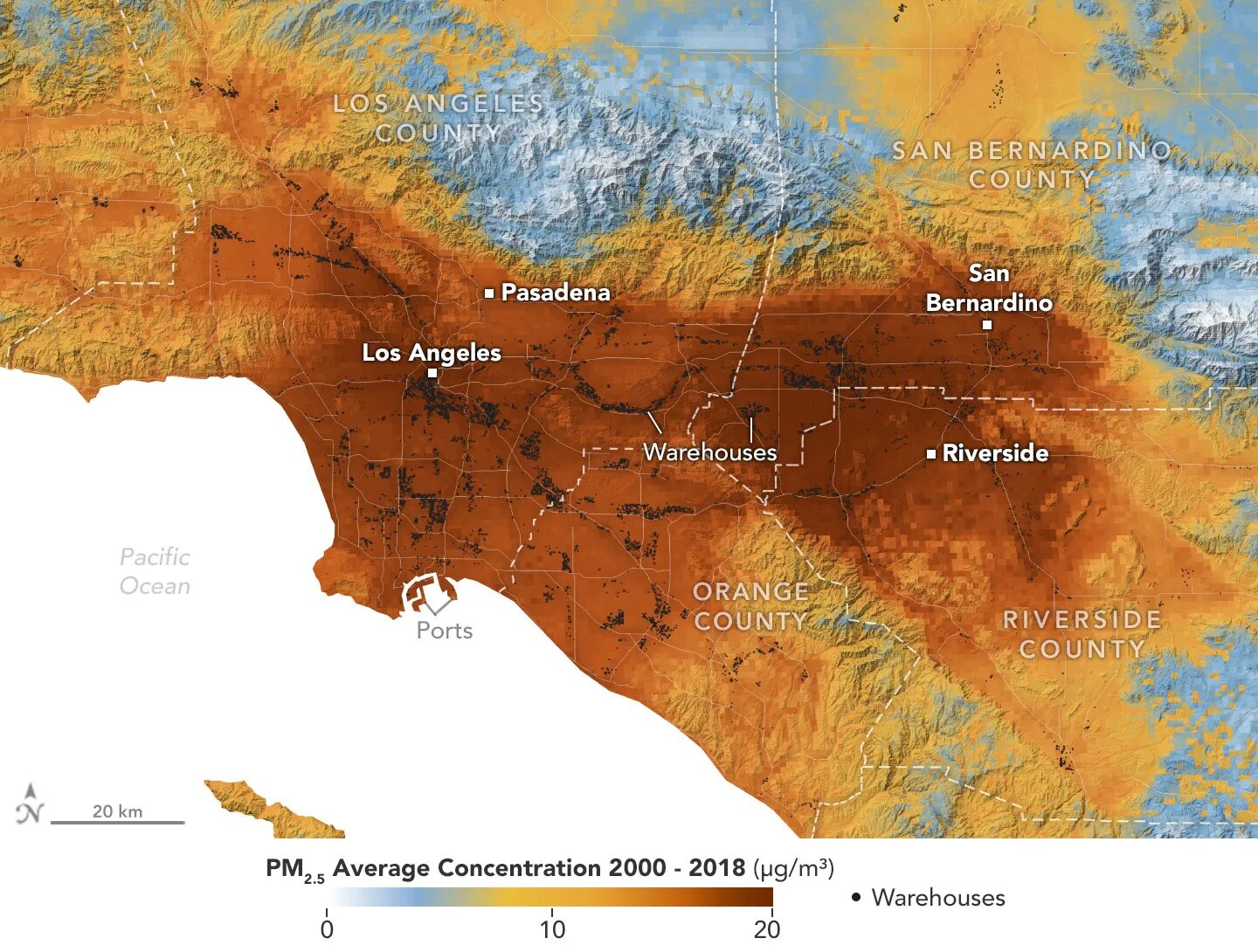

Published in the journal GeoHealth, the research analyzes patterns of particulate pollution in Southern California and found that ZIP codes with more or larger warehouses had higher levels of contaminants over time than those with fewer or smaller warehouses. Researchers focused on particulate pollution, choosing Southern California because it is a major distribution hub for goods: Its ports handle 40% of cargo containers entering the country.

The buildings themselves are not the major particulate sources. Rather, it’s the diesel trucks that pick up and drop off goods, emitting exhaust containing toxic particles called PM2.5. At 2.5 micrometers or less, these pollutants can be inhaled into the lungs and absorbed into the bloodstream. Although atmospheric concentrations are typically so small they’re measured in millionths of a gram per cubic meter, the authors caution that there’s no safe exposure level for PM2.5.

“Any increase in concentration causes some health damage,” said co-author Yang Liu, an environmental health researcher at Emory University in Atlanta. “But if you can curb pollution, there will be a measurable health benefit.”

Growing air quality research

Particulate pollution has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, some cancers, and adverse birth outcomes, including premature birth and low infant birth weight.

The new study is part of a broader effort to use satellite data to understand how air pollution disproportionately affects underserved communities.

As the e-commerce boom of recent decades has spurred warehouse construction, pollution in nearby neighborhoods has become a growing area for research. New structures have often sprouted on relatively inexpensive land, which tends to be home to low-income or minority populations who bear the brunt of the poor air quality, Liu said.

Another recent study analyzed satellite-derived nitrogen dioxide (NO2) measurements around 150,000 United States warehouses. It found that concentrations of the gas, which is a diesel byproduct and respiratory irritant, were about 20% higher near warehouses.

Distribution hub

For the GeoHealth paper, scientists drew on previously generated datasets of PM2.5 from 2000 to 2018 and elemental carbon, a type of PM2.5 in diesel emissions, from 2000 to 2019. The data came from models based on satellite observations, including some from NASA’s MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) and ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer) instruments.

The researchers also mined a real estate database for the square footage as well as the number of loading docks and parking spaces at nearly 11,000 warehouses across portions of Los Angeles, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties, and all of Orange County.

They found that warehouse capacity correlated with pollution. ZIP codes in the 75th percentile of warehouse square footage had 0.16 micrograms per cubic meter more PM2.5 and 0.021 micrograms per cubic meter more elemental carbon than those in the 25th percentile.

Similarly, ZIP codes in the 75th percentile of the number of loading docks had 0.10 micrograms per cubic meter more PM2.5 and 0.014 micrograms per cubic meter more elemental carbon than those in the 25th percentile. And ZIP codes in the 75th percentile of truck parking spaces had 0.21 micrograms per cubic meter more PM2.5 and 0.021 micrograms per cubic meter more elemental carbon than those in the 25th percentile.

“We found that warehouses are associated with PM2.5 and elemental carbon,” said lead author Binyu Yang, an Emory environmental health doctoral student.

Although particulate pollution fell from 2000 to 2019 due to stricter emissions standards, the concentrations in ZIP codes with warehouses remained consistently higher than for other areas.

Researchers also found that the gaps widened in the holiday shopping season, up to 4 micrograms per cubic meter—”a significant difference,” Liu said.

Satellites provide big picture

Satellite observations, the researchers said, were essential because they provided a continuous map of pollution, including pockets not covered by ground-based instruments.

It’s the same motivation behind NASA’s TEMPO (Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution) mission, which launched in April 2023 and measures air pollution hourly during daylight over North America. The release of TEMPO’s first maps showed higher concentrations of NO2 around cities and highways.

Meanwhile, NASA and the Italian Space Agency are collaborating to launch the MAIA (Multi-Angle Imager for Aerosols) in 2026. It will be the first NASA satellite mission whose primary goal is to study the health effects of particulate pollution while distinguishing between PM2.5 types.

“This mission will help air quality managers and policymakers conceive more targeted pollution strategies,” said Sina Hasheminassab, a co-author and science systems engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. Hasheminassab, like Liu, is a member of the MAIA science team.

More information:

Binyu Yang et al, Impact of Warehouse Expansion on Ambient PM2.5 and Elemental Carbon Levels in Southern California’s Disadvantaged Communities: A Two‐Decade Analysis, GeoHealth (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2024GH001091

Provided byNASA